Jacques-Edouard Berger

Lectures Pour l'Art

Lectures cycles developed along three parallel axes: - the continous analysis of major movements, trends, and schools punctuating the course of history - the analysis of certain major centers and sites which, through their importance, presided over transmutations in the realm of the aesthetic, - the in-depth study of artists, painters, sculptors and architects whose work provides keys.

Each cycle mentioned consisted of fifteen lectures:

- Enigmas in Painting - Fifteen Works Seeking our Gaze*

- The Forgotten Pathways (Architecture and the Sacred)*

- The Key to Looking (Major Schools of Painting)*

- The genius loci (Garden Architecture and Art)*

- Fifteen Pharaohs in Search of the Absolute**

- Art and Civilization of Classical India**

- Art and Civilization of Classical China**

- Splendors and Miseries of Genius (1780-1880)**

- The splendors of the Baroque Styles*

- Art and Civilzation during the European Renaissance*

- The Art and Civilzation of Pharaonic Egypt**

- Japan: Art and Civilzation**

- The Art of India**

- Rocaille-style**

- The Dawn of a new World**

- Rome - The Paleo-Christian Era - Byzantium - The Early Middle Ages -The Roman Era - The Gothic Era**

- Prehistory - Egpyt - Greece**

*Lectures available on ![]()

**Not available for the moment

Section Museum

Photographic legacy of JEBF***: major Museums visited by J.E Berger. Access by Google Maps API.

Section Trip

Photographic legacy of JEBF***: major sites visited by J.E Berger. Access by Google Maps API.

Section Collection

The collection is dedicated to ancient Egyptian art (Predynastic Period - Old Empire - Middle Empire - New Empire - New Empire & Late Period - Late Period - Late & Greco-Roman Period - Greco-Roman Period - Coptic Period - 19th Century), to objects from Asia, Chinese (Shang Dynasty - Dynasty Western/Estern Zhou - Warring States Period - Han Dynasty - Wei Dynasty - Six Dynasties Period - Tang Dynasty - Song Dynasty - Yuan and Ming Dynasties - Qing Dynasty - 20th century) but also Indian (12th-17th century - 18th-19th century - 19th century - 20th century ), Tibetan, Japanese, Burma, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Nepal.

Collecting in the eyes of the world

Section Essay

19 essays to discover.

Contact

Fondation Jacques-Edouard BergerAvenue de la Harpe 12

Case postale 249

CH-1001 Lausanne

Switzerland

e-mail: fondationjeb@gmail.com

***Jacques-Edouard Berger Fondation

- Close

- Altdorfer Albrecht

- Biéler Ernest

- Bernini Gian Lorenzo

- Blake William

- Böcklin Arnold

- Bosch Hieronymus

- Botticelli

- Bronzino

- Canaletto

- Canova Antonio

- Carpaccio Vittore

- Cimabue

- Caravaggio

- Chardin Jean-Siméon

- Crivelli Carlo

- David Jacques Louis

- Delacroix Eugène

- Donatello

- Duccio di Buonisegna

- Dürer

- Eyck Jan van

- Fra Angelico

- Fragonard Jean-Honoré

- Friedrich Caspar David

- Füssli Johann Heinrich

- Ghirlandaio Domenico

- Giorgione

- Giotto di Bondone

- Gleyre Charles

- Goya y Lucientes

- Gozzoli Benozzo

- Greco El

- Grünewald Matthias

- Hogarth William

- Holbein the Younger Hans

- Ingres Jean-Auguste-Dominique

- Klimt Gustav

- La Tour Georges de

- Ledoux Claude-Nicolas

- Leonard de Vinci

- Limbourg Brothers

- Liotard Jean-Étienne

- Longhi Pietro

- Lotto Lorenzo

- Manet Edouard

- Mantegna Andrea

- Martini Simone

- Masaccio

- Memling Hans

- Menn Barthélemy

- Michelangelo

- Moreau Gustave

- Palladio Andrea

- Piero della Francesca

- Piero di Cosimo

- Piranesi Giovanni Battista

- Pisanello

- Pontormo Jacopo

- Poussin Nicolas

- Raphaël

- Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

- Robert Louis-Leopold

- Robert Hubert

- Romano Giulio

- Tiepolo Battista

- Uccello Paolo

- Velázquez Diego

- Vermeer Jan

- Watteau Jean-Antoine

- Zurbaran

Choose an artist

- Find artist's work

- Amarna, capital of the Disk

- Pilgrimage to Abydos

- Roman Portraits from Egypt: The eye and eternity

- The Symbolic World of Egyptian Amulets

- Art can, and should, inspire analysis

- Memphis

- Angkor - Divine Breath of Stones

- A visit to the stupa Borobudur

- The Enchanted Gardens of the Renaissance

- Shaanxi History Museum

- Ajanta

- Sandro Botticelli

- Caravaggio

- Georges de La Tour:An Itinerary in Light and Shadow

- The Dizzying Grandeur of Rococo

- Johannes Vermeer

- The Egg and the Pearl

- Venus and the Music of Titian

A. Collection Egypt

B. Collection China

C. Collection India

Jacques-Edouard Berger, born in 1945, died unexpectedly of a heart attack in the fall of 1993, midway in a career which had taken him by then to the four corners of the earth. From his earliest years on, his life had been totally absorbed by the pursuit of art and beauty. During a period as a curator of the Museum of Fine Arts in Lausanne, he was already active in organizing exhibitions and writing many articles and prefaces. But the world at large beckoned and, leaving his moorings, he set out and spent many months each year in traveling all over the world. He was particularly attracted to the ancient civilizations of Egypt, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Burma, etc., yet never neglected his European heritage as mirrored and celebrated in countless museums and galleries in Europe and the United States.

Jacques-Edouard Berger, born in 1945, died unexpectedly of a heart attack in the fall of 1993, midway in a career which had taken him by then to the four corners of the earth. From his earliest years on, his life had been totally absorbed by the pursuit of art and beauty. During a period as a curator of the Museum of Fine Arts in Lausanne, he was already active in organizing exhibitions and writing many articles and prefaces. But the world at large beckoned and, leaving his moorings, he set out and spent many months each year in traveling all over the world. He was particularly attracted to the ancient civilizations of Egypt, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Burma, etc., yet never neglected his European heritage as mirrored and celebrated in countless museums and galleries in Europe and the United States.

As the artistic leader and guide of numerous groups of eager admirers with whom he shared his vision and insights, he succeeded, over time, in creating a collection of well over 125,000 color slides, his own photographs, capturing the masterpieces that quickened his emotions. In turn, this unique treasure of his personal discoveries served to illustrate and animate the series of lectures he would give, between travels, to an ever growing following, lectures that, in focusing on the powerful revelation hidden in the works of art, sought to provide a veritable initiation. Two books "Pierres d'Egypte" and "L'oeil et l'éternité" also attest to this original approach and the acumen of his intuition.

The profound sorrow and distress caused by his untimely death prompted number of his friends and admirers to create the Foundation that bears his name and whose principal purpose is to promulgate the discovery and love of art.

World Art Treasures is a great, new undertaking to meet this challenge. In addition to the initially offered display successive programs are in preparation. They will deal thematically with the civilizations of Egypt, China, Japan, etc.

The important personal collection of rare artifacts will become the subject matter of special programs.

"There are men who have molded our consciousness: Confucius, Buddha, Plato, Saint Augustine, Leibniz, Newton, more recently Tagore, Einstein, Bohr.

There are works of art that have affected our vision to the point of transforming our way of perceiving the world.

Events, men and their creations have thus fashioned History.

But are not our creations, and more precisely our works of art, the most intricate and faithful evidence of our mutations ? "

The act of collecting has lead to many analyses -- anthropological, historical, financial and, above all, psychoanalytical. All these studies -- which acquired their first letters patent in Cicero's speeches denouncing Verres, or in Pliny's commentaries with respect to the taste the Romans cultivated for Greek works of art -- are both illuminating and unsatisfying. They only imperfectly translate what incites a being to need to possess objects chosen according to very specific criteria, and even more clumsily what qualifies these collections of objects, each in its own singularity. In other words, neither the act nor its result can be totally understood.

I am now addressing nonspeculative collections, motivated by other reasons than those of the market. The history of art is, of course, rich in large collections which were constituted for financial reasons or to acquire prestige. In these cases, there remains a mystery about the selection of art as the goal of a personal achievement, either for profit or the acquisition of rank. It is undoubtedly easier to collect real estate or stock market securities, not an entirely risk-free undertaking to be sure, but one which calls for other qualities than the essential one of vision. But speculative collections -- which we shall call those collections which have other goals than the simple possession of the coveted object -- have this in common: the selection can be delegated or even shared between several decision makers. The final proof of this was very recently seen in the invention of artistic investment companies, a phenomenon which grew out of the exuberant art market of the 1980s. But well before this explosion, history contains many examples of delegated collections, with, sometimes, it is true, a significant relationship of aesthetic complicity between the scout or beater, who does the spadework, who discovers, reports and proposes.

Nonspeculative collections cannot be delegated. They are the result of an impulse which directs the collector toward the object, which he alone can distinguish, and which he jealously keeps to himself. In this process, or tropism, there is no question of delegation, sharing or barter. To the extent that this type of collector, if he requests advice, does it less to be truly counseled than to put his own determination to the test; that if this collector should, moreover, accept an object as a gift, he will only truly appropriate it as his own if he had the prior intention of acquiring it -- albeit with less pleasure than if he had; that this collector will only divest himself of a piece of his collection for certain reasons, which are never primarily financial, but always emotional. The disavowal of an old purchase, viewed now as a youthful error, the need for more rigorous selection criteria, a faulty investment of desire in an object, or other similar motives, which can all be viewed as the inability of the object to be sacrificed to respond to its owner's imagination. The exception to this dynamic is also emotional, when a collector divests himself of a beloved object -- a very symbolic act -- to someone who then can, for a short time, share not the collection, but the associated fantasy.

These few introductory lines tend to confirm the psychoanalytical theories which have been advanced about the collection phenomenon. The emotional investment in the act of collecting is undeniable; moreover, it supports terms which reinforce this aspect. The collector "possesses," he is "avid," he is "jealous." He is moved by "desire." These few terms suffice to establish the range in which the "impulse," evoked above, is expressed. In addition, in the case of collections of works of art -- and not found objects -- they are put together with money. One pays to possess. There are too many clues which effectively corroborate the psychoanalytical theories for them to be denounced. The act of collecting is truly a diversion, a substitution, a sublimation or a perversion of instinctive and emotional needs. Having established this, what can, however, be qualified is the nature of the transfer that takes place as a function of the collections and collectors.

Although it was in his youth that he assembled his first objects, Jacques-Edouard Berger had not, at that time, "started a collection." He had other intentions. Along the way, he gathered fragments, vestiges and traces of human industry which caught his eye. Without discrimination as to period, technique or function, the slightest object endowed with the grace that enables a portion of the veil to be lifted, thereby revealing the aesthetics of a moment or a society's thought process, like a partial reflection glimpsed in a mirror, delighted him. It is true that what delighted him even more was the fact that he was capable (perhaps he alone) of perceiving an object's beauty, of understanding its message and of singling it out from its peers. A rococo console element in the form of a scroll, a Directoire sign on painted sheet metal, an art deco paperweight, sometimes lost amongst meager secondhand articles, which immediately called out to him, as though there were a visual language of desire, the codes of which he alone knew, but which one might be tempted to think was emitted by the object itself, some sort of radiation. In this constant exchange with the sign-bearing objects, collecting was not the goal, but the act of buying came from the collector's fantasy.

Traveling only reinforced this quest for the invested object. Jacques-Edouard Berger then discovered other vestiges, bearers of new messages about cultures of an even rarer happiness, because they were less obvious. At the frontiers of the European domain or the Mediterranean Antiquity, vast regions of thought and sensation stretched out, ready to be discovered, penetrated, acknowledged and integrated. Much as the Tibetan shaman's smock opens the imagination to new hypotheses on the channels of meditation which guide Man in his quest for holiness, so the miniature clay model of an abode from the great Chinese era offers a more pragmatic vision of the hereafter.

Amongst the regions of thought which Jacques-Edouard Berger explored, two civilizations were to play a predominant role: first Egypt, then China. The road of life traveled with Jacques-Edouard as a companion, an accomplice and a witness to his passion allowed me to share Egypt with him, but never China. It is thus only regarding Egypt's immensity that I can convey the memories which form the basis for these thoughts.

Traveling with Jacques-Edouard was not merely a physical displacement . From the time of the first Egyptian experiences in the early 1960s, the adventurous amateur who chose Voyages for Art as a means to an end, soon realized that at the expense of making an effort to give up comfort and at the price of some fatigue -- at that time, Egypt was not equipped for tourism as it has been since the 1980s -- what Jacques-Edouard was offering was not exactly tourism, but a spiritual journey. The body moved, was hot, was thirsty and suffered various ills; in return, however, it was buffeted by immense, emotional shocks: another culture's exoticism. By this, I mean contemporary Egypt, which Jacques-Edouard knew not to gloss over but, on the contrary, to help in comprehending and perceiving, to living in communion with the revelation of its beauty, violent in the contrast of its landscapes, in the intensity of its light, vibrating under a heat which one could not even think of escaping. After these "student" trips, always organized during the high summer months, which covered the entire Nile Valley for as much as a month, one came home with dry, chapped skin and a ravaged stomach, but already filled with the irrepressible desire to leave again to recapture the visual and spiritual fulfillment which Jacques-Edouard's Egypt offered, this unique sensation of having come face to face with a personal truth, well within any concept of culture.

Jacques-Edouard did not "guide" Egypt, he "saw" it and "talked" it. Led by his vision, the privileged traveler slowly penetrated the mysteries of a complex civilization, based on different values than those to which the West has given importance. The "knowledge" of the difference, however, is only possible if one accepts the notion of otherness. Jacques-Edouard spoke to this when he introduced one to Egypt as, for him, it was life's essential experience.

The ability to recognize this difference led Jacques-Edouard very far in the comprehension of what, for many learned people, remains in the domain of objective acquisition. His knowledge was also certainly fed by much reading and culture. But scholarship was never anything more than a verification, sometimes a posteriori, of another sort of communion based on vision and the sensitive, analytical ear, which he brought to emotions and the clear-sightedness provoked by the vision in his deepest being and conscience. Thus, an Egyptian temple which, for the majority of researchers and spectators, remains an archeological site or a witness to history, the history of religions or of art, was, for Jacques-Edouard Berger, above all a meeting place, where archeology and history are forerunners, but not the finality of the study. To follow him into the great courtyard of the Temple in Luxor did not only mean merely to appreciate Amenophis III's admirably designed layout, it was also, above all, an internal perception of Egyptian solar space.

In our rational societies, intuitions are signs of confusion. They are deemed suspect by the Academy and send the scholar who dares suggest them into exile. One might recall the ostracism of Schwaller de Lubitz, the Egyptologist who was tempted by the occult. To some extent, and paradoxically in view of the success his lectures enjoy, Jacques-Edouard Berger has suffered the same penalty, or should one use the word mistrust, by the College of Egyptology. For, in this contemporary world, the function of knowledge has increasingly become a type of military strategy, the construction of bastions of specialization, to which are brought the illusion that they will protect us from the indescribable, the unrepresentable and the full complement of existential fears and anxieties which naturally accompany it.

But has humanity ever been anything more than a lengthy questioning of fate? Were these civilizations which, today, no longer exist or have been radically transformed by modernity, yet still so important for our roots, exhumed for any other reason than the need to anchor in history the concept of continuity which, alone, makes the perspective of the biological term of any future life acceptable? Dead languages, vanished civilizations, the terminology bears witness to the implied corollary: "but we are still alive." Is it then justifiable to consider Jacques-Edouard Berger's passion for the past as an inversion of this relationship: "I accept my death, but I know that nothing of humanity really dies and that the word lives on."

"Life, health, strength, for eternity!" -- the few hieroglyphs needed to represent this invocation are nearly always present next to the pharaoh's image. One can content oneself with deciphering them and recording their frequency. One can also believe that they are still useful today, and this is undoubtedly what distinguishes Jacques-Edouard's approach and vision. By reading a dead language, one brings the past to life. Listening to what it has to say is to engage in a dialogue with a still extant reality. In this way, this rare privilege of an encounter was established, which Jacques-Edouard used throughout his life to nourish his thoughts and activities.

Jacques-Edouard Berger believed that the word from the past was transmitted not only by language, but by works of art, the "vestiges" we discussed earlier. These objects were not mute, but rich in various calls for attention. The beauty, the physical quality was certainly one of the aspects that caught his attention, but no more than a fracture, a chip, a mark marring perfection, a stigmata of an object's adventure through life, which says much about the precariousness of all material. Magic also, which he respected, as he had never succumbed to the illusion that objects from these civilizations, even uprooted or deteriorated, had lost the power of their meaning, nor that the act of possessing them constituted a castrating dominance.

The act of collecting had thus become justifiable for Jacques-Edouard Berger in his approach to the past. Attentive to what the objects had to say, one would not be far off the mark in saying that these speeches were addressed to him because he knew how to listen to them, and that he had been chosen by the object as its place of abode before he himself had made his choice. Endowed with very fine hearing, he sheltered an infinite variety of witnesses in his apartment, thus demonstrating his great eclecticism. From the purest classicism to the most fervent baroque, each "communicating" object found its place and its relationship, if he could make the encounter happen.

The fertile marriage of intelligence and sensitivity to the vestiges of the past allowed Jacques-Edouard Berger to assemble a very particular collection characterized by its aesthetic quality, accessibility and diversity and the singularity of certain choices. This book will serve as its catalogue and I believe it will make one aware of the extraordinary quality of the author's idea of vision and his ability to recognize the essence of things through form and materials. Before being considered as the manifestation of a need for appropriation, a collection of this type must be viewed as an act of mediation. A goodly number of the objects which make it up are, in fact, substitutes. But I think that I can safely say that they are not substitutes in terms of compensation, emotional or instinctual, as psychoanalysis commonly defines them, but temporal substitutes. Had he been able to do so, Jacques-Edouard Berger would have collected temples, from Abydos to Borobudur to Bramante's Tempietto. In his experience of spiritual life, so essential to him, the objects in his collection functioned as symbols and tools, symbols of the pact made with eternity and tools for communication with the otherness, from which he daily drew his self-awareness.

The collection pursues and will continue to pursue this mediatory function. It will bear double witness, both to the raison d'être of the people who preceded us, but also, and this is perhaps the most important purpose, to the nature of the relationship we can have with art. Jacques-Edouard Berger's collection can lead us toward the first condition for communication, bringing into play not only vision, oriented in a specific direction, but the fertile interaction of an eye which knows how to listen. In our modern world, invaded by universal images and sounds, where often contradictory messages smash into each other like galaxies, cultural identity, laboriously built up since the 19th century on historical consciousness in which the function of the monument is associated with the principle of collection, tends toward a profound modification of its meaning because of an excess of information. Commensurate with the planet-wide distribution of messages, with the computerized nature of its media, these take on a different "significance." This irreversible dynamic of the communication society is not only a system in and of itself; its consequences for the individual, his spirit, and his awareness, which are still difficult to measure today, are undoubtedly far more important and definitive than one might imagine. In this identity, tending toward the global, the individual is seeking recognizable signposts. A first answer is supplied, he believes, by culture. Culture, however, is part of the communication system.

Jacques-Edouard Berger was aware of this. Although a user of this system, he knew how to maintain his mastery and utilize it to pursue his spiritual goals. A cultural guide in all the senses of the term, he led his protégés beyond culture, toward art. His travels and his lectures allowed him to communicate in his own words the messages he heard from works of art. But, before communicating, and to understand the murmuring of the objects, he knew that he had to remain silent in order to listen to the serenity of temples, the silence of materials, and the mute words of forms. For those who know how to remain silent and listen, the collection speaks today on his behalf.

Claude Ritschard

Enigmas in Painting

Every painting is an enigma. No matter what motif the artist chooses, the artist's eye sees beyond the limits of reality, beyond what is commonly designated as "reality." For it is here that the creative adventure has its starting point: Mont Saint-Victoire is an arid heap of loose stones, but Cezanne transforms it into a marvelous microcosm, disclosing stone in its original state, shaped, crumpled, and crushed by the genius of the creator and the very paste of his brush.

Herein, then, lies the true miracle of art, namely that of turning the commonplace into the sublime, the mediocre into the absolute. Ingres's Madame Moitessier, the upper class daughter of a high ranking government official (Water and Forests Dept.), was no doubt a good wife and mother, a little thick- waisted as was the fashion at the time, with a placid gaze and gestures as slow as her passions. But her supreme effigy at Washington D.C.'s National Gallery has her transformed into a sovereign Juno, with skin so smooth that centuries of wear have been - and will continue to be - unable to alter her deliberately obvious beauty.

Other paintings are just as enigmatic: Fragonard, for example, object of the public's adulation for his masterful depictions of frivolities, is known to have abandoned his elegant, rapid and often caustic brushstroke in order to transform a Fête de Rambouillet into a dizzying stroll along the swirling rapids of a darkly shaded Styx. Or Klimt, master of the Byzantine-Japonizing effects of "Secessionist" Vienna, who was wont to adorn forest and glades, flower plots and rock gardens with interlacings as skillful and shimmering as those with which his beloved lady friend Emilie Flöge graced her suitors.

In one case, the painter's entire career remains a mystery: Bosch the first, whose wild visions fuel debate among critics still today. One wonders, are these the fruit of troubled sleep or psychotic dreams? Do they imply hermetism to which there exists a key, or an encoded message? In a far solar language, Giorgione remains just as incomprehensible, given the degree to which he had assimilated the erudite humanism of Venice, whose very rules we have since lost.

And, finally, El Greco comes to mind: his exaggerated mannerism can certainly not be attributed to a defective vision but, rather, can be explained as an expression of the impact of a cultural clash between the artist's Cretan and Byzantine origins and his training in the higher spheres of the Renaissance in its prime.

This semester's course does not promise to answer all these enigmas. Instead, it proposes a questioning of fifteen works in their original context, in an attempt to achieve a below-the-surface understanding of them in the light of their era - the ideas, beliefs and cultural contexts connected with their creation. A 15th-century native of Florence would not have the same approach to the painting of his time, his "contemporary painting," as would today's museum visitor. Consider Botticelli in the light of the Medicis at the height of their glory, the rise of Cosimo and Lorenzo, the triumph of humanism, the Church crisis instigated by Girolamo Savonarola's first sermons. At the time, Botticelli was a painter upholding a new ideal, a committed ideal, instead of merely the melancholic bard of Madonnas and evanescent nymphs.

You might say that we intend to take a "polyphonic " approach to art, without losing sight of the fact that enigma characterizes many other dimensions of art:

- the unstable world of attributions: the question of how it is affected by various discoveries, as in the case of the Louvre's The Concert, first attributed to Giorgione, in obedience to tradition, and recently re-attributed to Titian;

- iconography and its mysteries: the question of how to identify the subject matter of a painting with respect to the milieu in which it came into being, as in the case of the major landscape /Summer, from The Four Seasons/ at the Louvre, into which Poussin - succumbing to the appeal of classicism like so many of his contemporaries - introduced key elements stemming from the myth of Orpheusand Eurydice;

- the shadow and light of genius: the question of why certain artists - Bouguereau at the end of the 19th century, for instance - were worshipped as demigods of painting, only to fall into complete oblivion upon their death. Meanwhile, others - Georges de La Tour, for example - suddenly reemerge to be consecrated well beyond their wildest lifetime dreams.

The splendors of the Baroque and Rococo Styles

The history of the Baroque and Rococo periods is written in letters of marble, jasper, bronze, and stucco in all the capitals of the newly emerging Europe: in Rome, in the form of the monumental colonnade built by Bernini as the p ropylaeum to St. Peter's; in Prague, on the Charles Bridge, where Braun, Brokoff, and their pupils produced a multitude of effigies of the patron saints of Bohemia; in Vienna, where the perspective from Schönbrunn Castle stretches as far as the Gloriette - that landmark imperial arcade built by von Hohenberg as a symbol of the infallibility of sovereigns; in Berlin, Paris, Madrid, and even in the tree-shaded valleys of friendly Bavaria, where swarms of stucco putti sing out the joy of celebrating the divine order of all things.

The centers of the Baroque style are disconcerting to visitors; the sheer size of the building sites and the audacity of their design can leave one speechless. It could be said that this came to be because the sun was at its zenith during the 17th century, thanks to Louis XIV, and because the lights of reason crowned the reign of Louis XV during the 18th. We are almost tempted to overlook the fact that in 1660, the King ordered Pascal's Provinciales to be burned, while in 1752, his successor condemned the Encyclopaedia! One possible conclusion to be drawn from this is that darkness is closely related to light. Perhaps Caravaggio sensed as much when, at the dawn of the century, he came up with the technique of chiaroscuro, that impassioned duel between night and day lying at the very heart of Baroque drama.

For the Baroque style, and later the Rococo, were indeed theatrical, with full mastery of contrary complementarities: the empty exalts the full, the full confers resonance on the empty; scrolls and interlacemotifs bring the pure and austere verticals and horizontals to vibrant life; light exorcizes shadow; goldmakes white reverbrate to the point of incandescence.

Fifteen sites, under the auspices of fifteen key works, will thus inspire us to travel through Europe, from Rome during the reign of Sixtus V to the extravaganzas of Prussia's Frederic II, with a few specialstop overs of a particularly unusual or appealing nature, such as the Bethlehem forest area in the heart of Bohemia, where a masterful sculptor carved tortured rocks into faces of hermits and ascetics; or Villa Palagonia in Sicily, surrounded with legions of sniggering and grimacing monsters commissioned by an enlightened prince.

On the way, we will rediscover those absolute masters whom we all too often forget, and who also played a major role during their time: Zurbarán, Velazquez, Poussin, Rembrandt and Vermeer. In other words, the history of the Baroque and Rococo styles, too, deserves to be written in capitals!

The Keys to Looking

"In the words of Horace some two thousand years ago, "Painters and poets possess the ever constant right to dare everything."

Twenty centuries later, his remark remains strangely valid, for painters and poets have retained not only their right, but their mission to dare. The privileged nature of their gifts, which we commonly refer to as their genius, confers upon them this inevitable and seemingly destined power to constantly adventure beyond the everyday. In so doing, they sweep us along with them, leading us towards other coun-tries, opening our eyes to other worlds.

In their creative surge some were carried by the enthusiasm of the crowds, of their friends, of theirpatrons, at times of a whole city. In one chronicle, for instance, we read that the great Duccio's Maesta Altarpiece crossed the city of Siena in the form of a triumphal procession, on its way to the artist's studio at the Town Hall where it was to be installed. Later, Raphael painted Julius II's Apartments in a theretofore unheard-of atmosphere of celebratory veneration. And it is alleged that the enthusiasticpainters who were allowed to assist Vermeer did so as if participating in a church service.

But the right proclaimed by Horace was not always appreciated with such serene equanimity: artists often tend to disconcert their contemporaries, to clash with their traditions, undermine their convictions. In such cases, a scandal crops up, a famous scandal which, one or two generations later, at the same time asserts and supports its author's glory: an Empress's fan slap to Olympia's bosom was enough to ensure the start of Manet's posthumous fame, the reproving fainting spell of a Lady in front of Fuseli's Macbeth won the artist the jealous respect of the gentry. We can even imagine how much comment Giotto's implacable message to the Scrovegni [cf the Scrovegni Chapel frescoes] must have aroused atthe time among the faithful.

Whether subjected to praise or obloquy, artists and their works are both the catalysts and the revealing agents of our society.

Fifteen major painters, fifteen master paintings, are the focal point of this semester's lectures. They will provide keys to understanding the evolution of various cultures, the intellectual movements in various societies, the reactions of artists who have sometimes been friends and more often rivals, the turns and turnabouts of art criticism - all this during six centuries in the history of Western cultural awareness.

The genius loci

"No one denies that some places are "inhabited."

The astrological events celebrated in the Room of Months of Ferrara's Schiffanoia Palace, the pathways lined with sphinges [lion-bodied sphinxes] at Tivoli's Villa d'Este or, further away, the precious pavilions of the residence of Emperor Qianlong in Peking's Forbidden City, are all peopled by jinni. Visitors lost in thought as they stroll through these sites cannot help but feel their presence and powers from time to time.

Dream power, the power of enchantment, of illusion... Here a fountain, reaching sky-high, with, in the middle of its miniature cascades, a gilt-bronze crown bearing the fragile flame provided by eleven candles; there an honor salon with a classical layout, a whole section of which collapses thanks to a miraculous trompe-l'oelig;il - apocalypse as a sort of joke; or, there again, the play of shattered mirrors embedded in the gold of the stucco work, distorting reality, shattering and fragmenting it, recomposing it according to whim, reflecting it ad infinitum.

At such times, then, the genius loci awakens, a goblin who smiles at our state of confusion, laughs at our apprehensions, and revels in our pleasure.

In order for the goblin to be born, in the fashion of the mandrakes in the fairy tales of yore, there must be the "alchemical" union between an inspired patron - emperor, prince, cardinal, margrave (all those whom Voltaire enjoyed deriding once he had stuffed himself at their table), or simply millionaire - and an artist, that is, someone capable of producing the sort of visionary work that does justice to the laws of perspective and of gravity, someone who can accomplish miracles - in short, a magician. Several such sites exist still today, and they have lost nothing of their magic spells. It is with an eye to discovering fifteen of these that we invite you to join us this semester.

From the Renaissance to present times, from nearby Bavaria to the furthermost bounds of India and China, we shall, in successive stages, regain the sublime privilege of dreaming.

Art and Civilzations during the European Renaissance

A strange idea, indeed, is that of rebirth, or "renaissance"...Above all, the term is two-faced: reassuring and worrisome at once. Reassuring inasmuch as it encompasses searches, intuitions and illuminations that allowed Western man to forge an identity to which heclings still today. But worrisome, too, as we become aware in our museum visits, when dialoguesbetween various works bring up paradoxes that remind us of just how fragile that identity is. Nothing could be more solar than the smile on the Mona Lisa, nothing more lunar, nocturnal and mysterious than that on Piero di Cosimo's Venus. Yet both were painted during just about the same year. Undoubtedly, this is the sort of paradox that gives the full measure of the greatness of the Renaissance. Fifteen masterpieces -paintings, sculptures, goldsmith pieces - will guide us along: each one will reveal an interesting aspect of our approach.

Thus, Piero Delia Francesca's Ideal City will break the silence of its deserted squares to speak to us about perspective; the finery on Carpaccio's Two Courtesans will illustrate the tastes developed by ducal Venice for the splendor of the Orient; and the salt-cellar offered by Benvenuto Cellini toFrancis I will serve as an emblem of the primacy granted by artists to the exhilarating frenzy of ornamentation. Together, we shall travel the cities that were the birthplaces of "homo novus," the new man: Mantua, Ferrara, Verona, Padua, Venice, Florence, Rome; there we shall encounter the haughtiness ofthe patron-princes, lawmakers, tyrants or condottieri- the Gonzagas, the Estes, the Farneses, the Medicis- side by side with those who immortalized them: Mantegna, Botticelli or Bronzino. We shall view the famous works dedicated to them, such as Paolo Uccello's San Romano Battle scenes, and the lesser known ones such as the sibyls [Room of Sibyls] in the Casa Romei in Ferrara, creatures who - it is rumored - caught the eye of Lucrezia Borgia when she sought haven at that peaceful site. For over a century now, we have been questioning the Renaissance. But despite all the brilliant works this has inspired - by Jacob Burckhardt, Bernard Berenson, Roberto Longhi, Andre Chastel, to name but a few - we feel sure much still remains to be discovered.

The Forgotten Pathways

Certain events have proven history-making: the unification of the Indian subcontinent under the aegis of Emperor Ashoka, during the 3rd century BCE, for instance; the opening of the Horse Road - the future Silk Road - by the Han sovereign Wudi; or, just before our era, the battle of Actium [31 BCE], the interview on the Field of the Cloth of Gold at Guines [1520], or the Declaration of the Rights of Man on August 26, 1789. And certain figures have shaped our cultural awareness: Confucius, Buddha, Plato, St. Augustine, Leibniz, Newton, and, closer to our time, Tagore, Einstein, Bohr.

Then, too, certain works of art have so imprinted themselves in our minds that they have transformed our perception of reality: the pediments by Phidias on the Parthenon; the journey along the Ganges carved by the Pallavas into the granite hillocks of the village of Mahabalipuram; the frescoes by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel of Padua; the Meninas by Velazquez; and up to Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon, which, in 1907, marks the birth of modern art.

Events, people and works are the stuff of history. But are not our creations, and more precisely our works of art, the most intricate and faithful evidence of our mutations? The bas-reliefs of the Temple of Amon in Karnak contain all the unswerving faith of ancient Egypt; Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel contains the fears, torments, shadows and hopes of the Renaissance at its crisis point; all the way to today's Grande Arche de la Defense, reflecting as it does the many challenges of our century.

But there are, too, more secret works, more remote sites. These are often left to the side, erased, as if the very singularity of their message is enough to frighten us away from them. So it is in China, where every year thousands of visitors visit the terraces, courtyards and pavilions of the Forbidden City, bedazzled by the sacred splendor unfurled there by the last of the Qing; but few will visit Chengde, yet so close, where dark and oppressing temples allow all the anxieties of the dynasty to well up. So it is in India, where crowds jostle at Udaipur to merge for a fleeting moment with the dream-inspiring white marble rendered sublime by the reflections of the water; yet no one stops off at Orchha (by the way, where is Orchha ?), as arid and severe as it arguably is but so revealing of the spiritual depth of the Rajputs, who fiercely rejected all the affected tastes flaunted by the royal court. People will endure hardships to reach the holy site of Angkor, while forgetting all the temples that the Khmers built along the plains of today's Thailand and Laos - temples that are especially fascinating when one realizes that the faces of the gods had to be remodelled to fit in with both the dogma of the conquerors and the secular beliefs of the latter's subjects.

This semester we shall explore together several of the remote valleys where History allowed itself to be forgotten.

A 2004 text which is still an appropriate introduction to the genesis of the World Art Treasures project

1994-2004: Towards a new World View - René Berger (1915-2009)

To say that a new world view is coming into existence is not saying much, unless we hasten to add that, for the first time, the view in question is truly universal. Indeed, it is not rooted in any of the outlooks once imposed by different empires of the mighty: Egyptian, Roman, Chinese or even Napoleonic. Nor does it stem from any religious hegemonies, whether poly- or monotheistic. It has no links with political ideologies, with any Marxist/Leninist trends of the sort that, at one point, looked like they would dominate the world. And it is equally unrelated to the neo-liberal view attached to the globalization that is a direct product of the free market economy. At another level, one might also put forward some connection with the views bequeathed to us by science, such as the rationalism of Galileo and Descartes, in conjunction with numerous technical inventions. The latter include the clocks and watches which, over such a long period of time, lent credence to a mechanistic view of the world. Only today has the resulting reductionism gradually begun to loosen its grip on us. In short, the new world view I have in mind has nothing to do with the "traditional" Weltanschauungen. It comprises no new representations or content matter, as might well be expected, but a process of emergence that resists definition - not for lack of information, but because that very information is undergoing massive changes.

As circumstances would have it, the whole story begins with a man -Tim Berners-Lee, a consultant with the CERN - and a dream: the dream of an instrument, the "Web," capable of linking together more than just the men and women who pioneered the Internet for military, scientific and academic purposes. Instead, he dreamt of a "World Wide Web" for the population in general, linking person to person, group to group, anytime and anywhere in the world: "The fundamental principle behind the Web was that once someone somewhere made available a document, database, graphic, sound, video or screen at some stage in an interactive dialogue, it should be accessible (subject to authorization of course) by anyone, with any type of computer, in any country. And it should be possible to make a reference - a link - to that thing, so that others could find it." (Weaving the Web, Orion Business Books, 1999, p.40). The author goes on to underscore the philosophic impact of this undertaking: "This was a philosophical change from the approach of previous computer systems." (ibid.)

The project was, and to this day remains so novel that, already at the time, Tim Berners-Lee felt free to assert: "Getting people to put data on the Web was a question of getting them to change perspective, from thinking of the user's access to it as interaction with, say, an online library, but as navigation through a set of virtual pages in some abstract space." Hence, it is the interaction between the "users" themselves and technology that constitutes, not the content of the view but, and more importantly, its raison d'être and the conditions enabling its realization as a living experience.

A further consequence - difficult to fathom, let alone accept, especially for authorities of all stripes - is not so much that the Web eludes all supervision, as some were quick to suspect and by the same token to condemn, but that it escapes that supervision by its very nature and ambition: "There was no central computing 'controlling' the Web, no single network ... not even an organization anywhere that can 'run' the Web. The Web was not a physical 'thing' that existed in a certain 'place'. It was a 'space' in which information could exist." (ibid p.39) (the single quote marks are my own emphasis).

Thus the Web is not to be confused with a data base, no matter how gigantic its scope. And even if it can be used for all the classical purposes, which it then augments thanks to its exponential power of calculation, it can never - and this is worth repeating, given how deeply ingrained our mental habits are - it can never be reduced to being a mere extension of the traditional structures. In short, it is always in the process of being reinvented.

Yet someone out there has to keep track of the latest developments. The review Flash Informatique, created to fulfill that purpose, offered Jacqueline Dousson occasion to address the question "Mosaic, vers une nouvelle culture?" (Mosaic, towards a new culture?) in its February 1994 issue: "Imagine that you are in front of your screen, that you click and read the latest news bulletin issued by the Pittsburg Supercomputing Center, that you click again and consult various works put out by the publisher O'Reilly, and that, with still another click, you land at MIT? Today, this is a reality, you can access all that and much more still." Dousson went on to point out the decisive role belonging to Mosaic, a project developed by the NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications) in Champaign-Urbana, as one of the first browsers to grant the masses access to the Web. And, finally, she asked "And what about the EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) in all this? Although the EPFL has already finalized its presentation 'for the initiated' (http://www.epfl.ch/ [...] the goal to be reached is that from no matter where in the world, by being linked to the Internet, one will be able to know what the EPFL is, what is being done there, whom to contact."

Certainly, at the time of the article - that is, a mere ten years ago (as the stipulation "for the initiated" attests) - no one, not even the article's author, could guess that the "new culture" to which a question mark was attached would not only develop but actually change the course of the entire planet with its explosion of ever more numerous and efficient networks. No one except a Bill Gates! Noting in its issue of November 3, 1994, that "the emergence of Mosaic and the World Wide Web is the most exciting development in a decade,"the International Herald Tribune goes on to comment with remarkable clairvoyance: "Microsoft has already begun to purchase reproduction rights to the masterpieces of the museums all over the world to produce specific CD-ROMs on art (among others those of the National Gallery of London). The openness of INTERNET through WWW is one way; the commercial way of Microsoft is another. At this point, it is not to me to judge; both are surely shaping our future, but questions are raised and initiatives should be taken."

I deliberately draw the reader's attention to this last highly significant remark. The future of the Internet was to be decided on the basis of a trend characterized by heretofore unprecedented complexity. It would be an oversimplification to reduce that trend to mere commercial ends. By painful coincidence, it was during this same period - late in 1993 - that the life of our son Jacques-Edouard Berger, born in 1945, was abruptly interrupted by a heart attack. During his all-too-short lifetime, devoted entirely to art, his thirst for knowledge had driven him almost all around the world. During his travels he collected numerous artworks with which he built up a private collection, while at the same time he served as travel guide to private groups, introducing them to the ancient civilizations to which he was particularly attracted - Egypt, China, India, Japan, Burma, Laos, and Thailand - together with a good number of locations in Europe and the United States.

While sharing his discoveries and enthusiasm with others, he unflaggingly photographed the sites and works encountered along the way. He thus assembled over 100,000 slides; these he subsequently put to use to illustrate his countless classes, lectures and publications. In the words of Jacques-Edouard himself, "Are not our creations and more precisely our works of art the most intricate and faithful evidence of our mutations?"

The prospects offered by the Web at that very time having come to our attention, it was thus in June of 1994 that we joined forces with the EPFL - in particular, with Francis Lapique - to create the Web site "A la rencontre des trésors d'art du monde / World Art Treasures." From the outset, we noted: "Taking advantage of the multidimensional specificity of the network, our intention is to shed a new light at the same time on art itself and on the manner in which it is contemplated. In contrast to the usual manner, consisting mainly in establishing data banks in a historical or documentary vein, our goal is to design and elaborate a different approach for each journey. [The idea is] to take into consideration and underscore each time one particular aspect in order not only to provide information, but to prompt a new experience in harmony with the new technology." Of course this was in no way meant as a stab in the back to Bill Gates - as ridiculous as it would have been presumptuous - but to demonstrate that the Internet and Web encompass a variety of potential pathways. That, besides the economic imperative lurking in this technology, the networks offer opportunity and room for spiritual and artistic values as well.

The first of our "programs" was featured on the Internet as early as July 1994, very shortly after the Web and the browser Mosaic had come into their own. It provides an overview of the main forms of artistic expression in the countries so well-traveled by Jacques-Edouard (Egypt, China, India, Japan, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand). The second program, Pilgrimage to Abydos, looks to the Internet as a means of allowing visitors to relive the pilgrimage taken some 3000 years ago by Pharaoh Seti I to build a temple bearing his name at Abydos, one of the meccas of ancient Egypt - a pilgrimage that Jacques-Edouard Berger himself accomplished numerous times, as described in his book "Pierres d'Egypte" (Stones of Egypt). The challenge of this digital approach is that of reconstituting the itinerary of a pilgrim not only in abstract and intellectual terms but, still more, one could say "spiritually" and "existentially": The trip is divided into successive stages leading from the first open-sky room all the way to the secret shrine inhabited by Osiris, Isis and Horus. In other words, the "pilgrims" visiting the site are invited to rediscover the process of being initiated, not only through words and images but by being subjected to an inner experience mirroring their virtual stage-by-stage screen trip. The paradox here, deliberately and duly considered, is that of resorting to electronics to produce a progression akin to an actual spiritual experience. It is as if the network, by freeing itself of defined space - or, at the least, from the primacy of a space where signs and images are traditionally inscribed - were freeing time into the flow of an initiatory journey. As if, too, it were rendering perceptible the feeling, or intimation, of the sacred.

These first shared treasures soon sprouted a whole series of offshoots: Roman Portraits from Egypt in January 1995, Sandro Botticelli in May 1995, A Shared Vision in December 1995, Enchanted Renaissance Gardens in March 1996, Vermeer in June 1996, Angkor in May 1997, Dizzying Grandeur of Rococo in May 1997, Georges de La Tour in September 1997, Borobudur in December 1997, Caravaggio in March 1998 - programs that are already past history in the light of all the subsequent advances in technology. Surprisingly and endearingly, right from the start this innovative undertaking enjoyed the warmhearted and very diversified collaboration of a wide circle of friends. It was they who, among other things, saw to the digitizing of several thousand slides, the gradual addition of legends, and the researching and verification of all the sources. More recently, in view of the progress in the software realm, they have also seen to it that Jacques-Edouard's lectures could appear on the Internet, treating viewers to his brilliant commentary viva voce on various subjects of his choice and many of his travels. Not to mention, furthermore, the generous and dedicated work accomplished by the members of the Foundation Committee, including the much appreciated contributions of several temporary assistants. All of which brings us to the site as it exists today: "FONDATION JACQUES-EDOUARD BERGER: World Art Treasures."

It is a change in the very nature of the link that lies at the heart of the transformation taking place today. No being, from the simplest to the most complex, can survive in isolation. Links are the sina qua non of our existence, of all existence: endogenous in linking together the component parts of each organism, and exogenous in linking living beings among themselves with their environment. The driving force behind a link -serving at once as its inspiration, manifestation and realization - comes down to what could be termed the phenomenon of activation. In a nutshell, links exist inasmuch as they are activated. That is, inasmuch as they are experienced in the relationship between the subject and the "object" (thing or being) or, more exactly, their interaction.

Now, by definition, the Web serves to set up links from one end of the planet to the other, from the farthest reaches of our collective memory to the latest news of the day. And this with anyone at all, immediately, everywhere? So that at present we have a situation where a connection experienced in real time establishes a virtual world - a world no longer based first and foremost on past references, as has been our habit until now, but one that emerges at the same time as the link comes into being. Hence it is no longer necessary to depend on classical tools, methods and techniques such as art history and the books it yields. The Web enables the creation of a multimedia field in which we can at once immerse ourselves and play a part. Here lies probably one of the most significant benefits of World Art Treasures: The adventure on which the site's founders first embarked has now become an ongoing process of expansion and ever more in-depth discovery. One could perhaps even go so far as to say that, despite his physical absence, Jacques-Edouard has been "brought back to life" - not in the usual sense of the expression, but in the sense of a kind of "cyber-existence" in which all can share. We can see that new dimensions are emerging from our present-day world and its accelerated transformation. Today's young people imply as much when referring, for instance, to our exploration of Mars: "Maybe we all go into space but we go mentally, virtually, electronically. We don't go with our bodies. As the technology gets better, the virtual reality could get quite profound." (International Herald Tribune, January 28 , 2004). In the generations to come, humans will have to be in a constant state of becoming. And their becoming will come to pass only if they link up with others to accomplish actions interconnected with the ever-growing possibilities of the new technologies.

RB (janvier 2004) Translated from the French by Margie Mounier, March 2004

J.-E. Berger Foundation [fr]

World Art Treasures

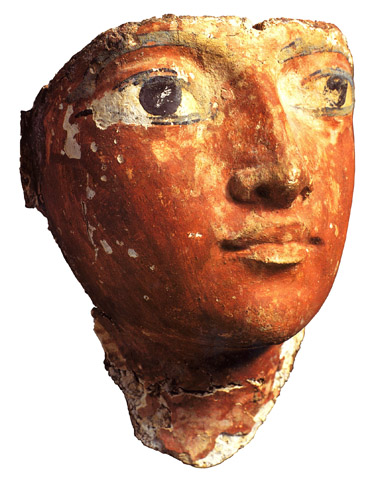

J.-E. Berger's collection (inv. 315)

Sarcophagus mask

Egypt - New Empire (Dynasty XVIII)

Stuccoed and polychromed wood - H 16.5 W 13 D 5.5 cm